Star House was built in 1889 by Texas cattlemen as a reward to Comanche Chief Quanah Parker for leading his tribe and the Kiowas and Apaches to enter a lease agreement for five North Texas ranchers to graze cattle on the reservation's vast sea of grass, with annual payments going to the Indians. Without the agreement, approved by the Department of the Interior in 1884, the three million acres of the Kiowa/Comanche/Apache reservation would have been tempting targets for ranchers looking for free grazing. Knowing that the army brass was not keen on turning their cavalrymen into cowboys to protect the Indians' grass, Quanah listened when approached with the idea of leasing the extensive grasslands of the reserve.

Burk Burnett, owner of the famous 6666 ranch, led the effort to construct a house befitting a man of Quanah's stature. Though the other four ranchers who leased the lush grasslands chipped in, Burnett bore most of the cost. His son Tom spent much of his early manhood living with Quanah, taken there by his father after the younger Burnett rebelled at his father's attempts to enroll him in West Point. Having dropped Tom off at the imposing academy on the Hudson, Burk went on to New York City on business. When he returned to Texas, he found his son had beaten him home. Out of frustration, and knowing that Quanah had taken several white boys under his wing, the elder Burnett took his son to Quanah to see what he could do with him. Quanah taught the younger Burnett the Comanche language and culture, and Tom taught Quanah the ins and outs of the cattle business. Over time the two became more like brothers than friends.

Another white boy strongly influenced by Quanah was David Grantham, who left his North Texas home and crossed Red River onto the reservation in search of Chief Quanah Parker. Grantham came from a poor family, and as a young man in his late teens, was looking for an opportunity to get ahead. Quanah's hospitality was legendary, and the Chief did not disappoint young Grantham, who became a member of Quanah's family. Within a year, the young Texan had become Quanah's secretary and business manager. While Quanah spoke English fairly well, he did not read or write, so Grantham read aloud to the Chief from the many newspapers and journals arriving at his post office box in nearby Cache, Oklahoma.

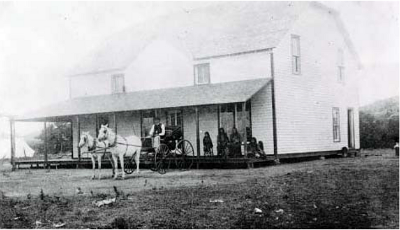

Burk Burnett worked with his son Tom and David Grantham in getting the two-story house built. The railroad had not yet reached the Fort Sill area, so lumber was hauled by double teams of mules from the railroad terminal at Harrold, Texas to the site where Star House was to be built about two miles north of Cache on a rise above West Cache Creek. Burnett and fellow cattlemen hired carpenters, and it is likely that Tom Burnett, David Grantham, and Quanah himself oversaw the work. The 12-room house was completed in 1889. At the chief's request, stars were painted on the roof to signify Quanah's rank as "general" of the Comanches. If the high-ranking military officers in whose circles Quanah moved with ease could use stars to signify their rank, so could the Chief of the Comanches. The Chief's stars, however, would not be displayed on his person, but on the roof of the imposing mansion befitting a man of Quanah's leadership abilities.

Distinguished visitors soon called on the legendary chief, formidable in war with lance and bow, yet gentle and hospitable in diplomacy; and what better place to entertain allies and win over would-be enemies than Star House. Among the notable guests of Quanah in Star House were British Ambassador Lord Brice; American President Theodore Roosevelt; Commissioner of Indian Affairs R. G. Valentine; Texas cattlemen Charles Goodnight, Burk Burnett, Tom Burnett, and Dan Waggoner; General Hugh Scott, General Nelson Miles, and General Frank Baldwin; Sioux Chief American Horse, Comanche Chiefs Wild Horse, Isa-tai, and Powhay; Apache medicine man Geronimo and other Indian leaders.

Hundreds of lessor known individuals also stopped by the imposing structure at the foot of the Wichitas. As the leading proponent of the Peyote religion, Quanah was known as much among the Indians on the reservation as a healer and a man of God as for his leadership as a politician and diplomat. People whose names would never reach the history books were welcomed by the half-blood chief who wore many hats while Quanah led Numunu, The People, on their forced journey from nomadic bison hunters to a sedentary life dominated by the Comanches' conquerors. Quanah's spiritual leadership was a balm to the Indians' souls, while Texas beef fed them, assuaging the gnawing hunger of the early reservation years. Star House was not just the home of Chief Quanah Parker, but a symbol of Comanche pride.

Quanah's son Baldwin, with his bride, lived in Star House with his father while his own smaller house was under construction a mile to the south. From the time the Chief's house was completed in 1889, extended family, whether by birth or adoption, lived in it or frequently visited. After Quanah's death in 1911, his daughter Neda Birdsong lived in the house until 1956, when Fort Sill expanded the artillery range to include the site of Star House. The Army moved the house next to the highway between Cache and the National Wildlife Refuge a short distance to the north. There it set until Herman Woesner, owner of Eagle Trading Post in nearby Cache, moved the house to his land about a mile west of the Trading Post. Other historical buildings were added, and rides were built to form an amusement park. Visitors could enjoy the various rides at the park and visit Star House on a tour conducted by Mr. Woesner.

Over the years, beginning in 1889, when the house was new, until the present day, Quanah and his descendants have had family gatherings at the house. Over time the once splendid home slowly deteriorated, the worst damage coming from a man-made flood from nearby West Cache Creek. Because the Comanche people have a strong attachment to the house, the tribe in July, 2015 asked for donations to help to save Star House. It had been a year since Parker family members or other tribal members could enter the house due to safety concerns. Though the flood had caused damage to furnishings in the house, including carpets, an architectural firm from Oklahoma City found the basic structure of the house to be in sound enough condition that it can still be restored. Ardith Parker Leming, great-granddaughter of the famous chief, says that seeing the house in its current state is heart-breaking. In its glory days, the Parker family hosted reunions, dances, and weddings there, including Ardith's own in 2006. "Star House," said Leming, "is a piece of my heart. All the furniture Quanah has sat on. That means something to my family. To step inside we know that is where we started, and we would like to see it restored to its former glory."

Many members of the Comanche nation, though not related to Parker, concur that the house represents a formative time in the history of the tribe. For a proud people who had once ruled the southern plains by means of military force, the defeated Comanches, deprived of their old life, saw Star House as a symbol of success during the reservation years. Their chief, unlike the leaders of most other plains tribes, prospered after the Indian wars. If Quanah could function in the white man's world, perhaps they could as well. Grass lease money distributed to every member of the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache tribes kept hunger at bay, and members of the three tribes had disposable income to spend, improving their quality of life.

The splendor of Star House contrasted with the half-dugouts and shacks of whites who lived on the reservation. All of the Indians as well lived in more modest housing, with almost all preferring life in tepees to houses. Star House was comfortably furnished. The table in the dining room could seat over twenty people. A white couple were servants of the Chief and his family. Quanah sat at the head of the table under a framed photograph of Theodore Roosevelt. If he wanted to call Roosevelt from Star House, Quanah could do so on his telephone, installed around 1909.

In the words of award winning journalist Charlie Clark of Durant, Oklahoma, "Star House is a historical and cultural treasure that needs to be preserved."

The above was researched and written especially for savestarhouse.com and Star House Preservation, Inc. by Bill Neeley. All rights reserved.